Luke Flowers offers some insights into honing your craft and the makings of a musician.

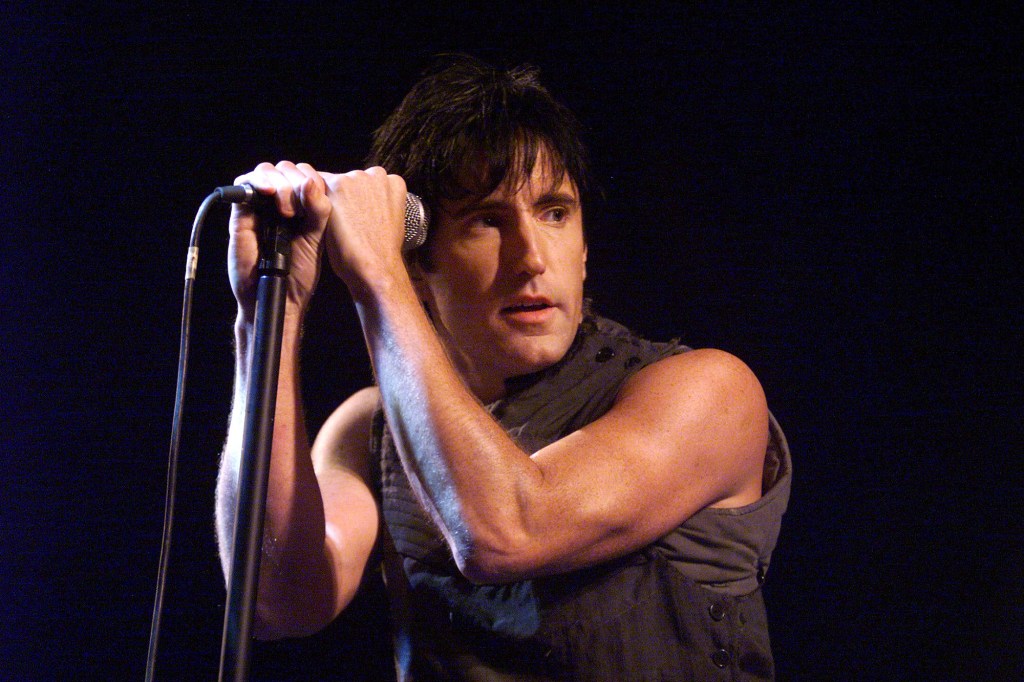

Feeling “revitalized” after two gigs in Tokyo with The Breath – and in the midst of an exciting tour with The Cinematic Orchestra – Luke Flowers sat down with me and discussed what makes a successful session drummer.

From an early age, Luke Flowers wanted to play music some sort of way but just “didn’t know how”. Then after an informal after-school lesson with a drummer he respected, Luke recalled how “I was hooked… drums are for me.”

I asked what the most important thing he did to get where he was today – Luke replied “a combination of really believing in yourself and just persevering”, going on to say how not believing in yourself fully means “you tend to not be as patient” and “end up maybe after a year or two thinking: ‘oh, maybe I’m not as good as I thought’”. Doubts, inevitably, will still creep in, but Luke argues there needs to be a spark, “something there that makes you carry on regardless”. Luke offers some insight into people he’s seen who perhaps don’t have that, commenting on how there’s a tendency to “not necessarily give up, but give up on their dreams”. Maintaining self-assurance is therefore instrumental in avoiding this situation.

Almost a pre-requisite for this line of work is enthusiasm, keeping engaged, and “just being into it”. When asked about touring, Luke commented on how it can be hard work, but one way he maintains a positive outlook is through “having that sense of adventure and being able to explore and experience new things”. Enthusiasm also paves the way for productivity. in his younger days more so than now, Luke would travel considerable distances to play any gig he could; it was all about “just learning and trying to soak it all up”.

One thing that separates Luke Flowers’ musical upbringing and the upcoming session players of today is technology. I asked him about the normalization of SPDs (electronic pads that are played alongside acoustic drums), and whether those who don’t embrace them become outdated. Luke offered that “the more things that you can do, the more enticing it is for people to book you”, so any technology you can incorporate into your playing is beneficial, however agreed it’s not mandatory for success in the industry.

Of course, the biggest technological change in recent years is the influence of social media – Luke adds “in some ways it’s easier, since you can promote yourself”, before highlighting that a challenge to overcome is how “there seems to be more competition”. Moreover, he notices how “people have less actual one on one contact” when promoting their musical ability online. This is something he can’t bear: “it’s one thing learning some fancy tricks and chops, but it’s another thing playing as a team”. Instead, enthusiasm and meeting people is “what it’s all about”.

It’s also important to stay loose stylistically. “The most important thing for me when I was starting off was playing as many styles, convincingly, as I could.” Luke admitted that wasn’t a business proposition, but simply out of love for music, however this lead him to meet musical people in several different circles:

“Keep your options open – try not to get too specialized too early – it’s good to keep a focus if you’ve got a band that you’re really into, but you can’t say ‘this is it’, otherwise you’re going to shut out so many other options.”

Overall, while “true skill and passion for music should be the most important thing”, Luke realises that “you can’t be a dreamer – you’ve got to keep working”. This is tough, but crucial, advice for anyone wanting to break into the session drumming industry, or really any creative career path. Regarding plans for the near future, expect more gigs with The Breath & The Cinematic Orchestra – specifically two big upcoming shows in Los Angeles, as well as a few in Ireland. Moreover, The Cinematics recently released their first album in over 10 years – 2019’s “To Believe” – prompting a 2-week tour of Eastern Europe. Trust me, when it comes to the session drumming industry, Luke Flowers knows his stuff.